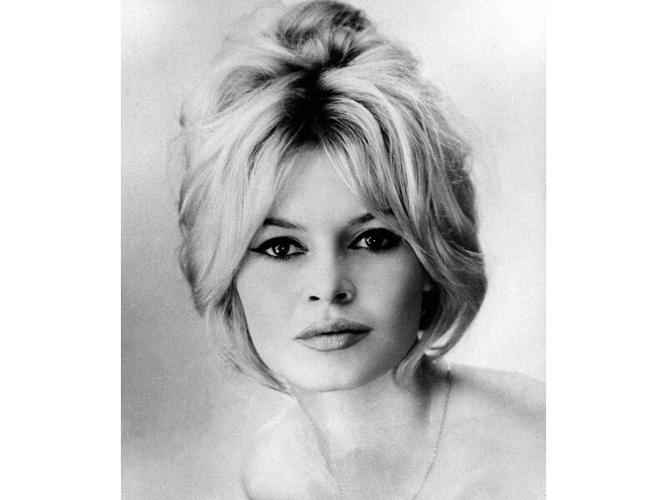

Brigitte Bardot could not be more fashionable this year. Actually, make that every year: her original and authentic presence and style has stood the test of time.

The sex symbol and superstar who exploded from the rocketship of French New Wave cinema is uncannily inhabited by actress Julia de Nunez in the new six-part fictionalized series “Bardot,” streaming on CBC Gem as of Friday.

The series begins just after Bardot has met Roger Vadim, who became her first husband (of four) and wrote “And God Created Woman” for her, which propelled her to worldwide acclaim — and scandalized many — in 1956.

A tightly crafted period piece, the early episodes detail the couple’s intense and illicit romance; Bardot was just 15 to Vadim’s 21. In contrast to the biopics of the moment that focus on character psychoanalysis and symbolism, this series is Euro-flavoured: subtle, textured, leaving motivations and morals in ambiguity, just like the New Wave era it documents.

De Nunez’s spot-on Bardot morphs from dutiful schoolgirl and aspiring ballerina to young woman in full possession and control of her sexuality. She is the pursuer in the underage relationship, standing up to her strict parents, putting her head in the oven in a dramatic (and successful) attempt to force them to allow her to see her older lover.

As writer/directors Danièle and Christopher Thompson point out in their directors’ note, the world wasn’t (and possibly still isn’t) quite ready for a woman with such a fiercely independent sense of self. She helped usher in the sexual revolution, but at a cost. “An unwitting advocate for freedom for the women of her generation, Brigitte pays dearly for her own,” they write. “She is idolized, hated, adored, despised, both the catalyst and the victim of this unprecedented outburst. The chase is on. From now on, there will be no end to the violation of her private life.”

Danièle told the Guardian earlier this year that when she wrote to Bardot to let her know about the project, Bardot replied saying if it was to be made, she preferred that Thompson be the one to do it, but “she was always surprised how unbelievably interested people were in her and did not quite understand why she was not left alone for good.”

After some 50 films, Bardot retired from acting in 1973 to become a singularly focused animal rights activist, another instance in which she was ahead of her time. But it led her to make Islamophobic comments regarding what she sees as cruel practices surrounding halal meat, and she has been charged in court with inciting racial hatred for it, multiple times.

Even so, her influence on fashion and the wider culture has been powerful. In 1969, she became the first real-life image of Marianne, the very symbol of the French Republic, carved into a bust.

Bardot had a preternatural sense of how to present herself, which is expressed in the series as rebellion against the way she was styled in her early films and modelling work. “I’d like to do my own hair and makeup my way,” she says. “I always feel disguised.” Once she bleached her hair blond, she created the “bedhead” look, a nod to the tousled, carelessly alluring style that became synonymous with French women‘s style.

Bardot has said this was not premeditated; she threw on what she felt in the moment. “The Bardot style is simply my own style; in other words it’s not a style at all,” she wrote in the introduction to the book “Brigitte Bardot: My Life in Fashion,” by Henry-Jean Servat. “I wore elegant gowns designed by the top couturiers, as well as gorgeous gypsy outfits that were unconventional, things I came across by accident and then became fashionable. It makes me laugh!” She added that she felt proud of creating a look that will never go out style—“because I was never fashionable!”

Much self-possession is necessary to have this opinion while creating the mythology of an icon. The signatures Bardot adopted and popularized are still in style today: The black headband, a dancer’s accessory that swept the ’60s; the messily applied “slept in” smoky eye; the “nude” lip, wherein she eschewed lipstick and blush to keep the focus on her giant blue eyes.

As for clothing, her greatest contribution might be the ballet flat, which is enjoying a massive comeback at this very moment. Bardot famously talked French dance brand Repetto into making ballet shoes that could be worn outside; the Cendrillon model created for her remains available today. When she wore a fresh and simple pink gingham wedding dress to marry her second husband, Jacques Charrier, in 1959, she set in motion a craze that even ended up on Barbie dolls.

But her biggest contribution was fearlessly breaking with norms. Having made the louche, laissez-faire lifestyle of St. Tropez famous, she often walked around barefoot, even at the Élysée Palace. Jean-Claude Jitrois, who dressed Bardot in the ’80s, described her instinctive style as “chic-destroy.” He was quoted in WWD declaring that what young people are drawn to is the way she said “merde to the bourgeoisie.”

In many ways, Brigitte Bardot symbolized the woman so many of us long to be: free and daring, confidently breaking rules, secure in her own skin. This, of course, is an illusion. But it’s ever such an alluring one.